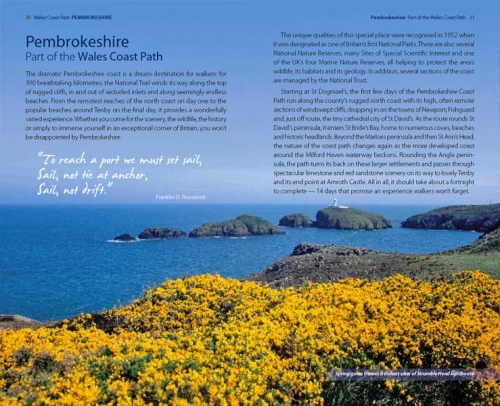

Pete Roberts riding a wave at Whitesands, in Pembrokeshire

Alf Alderson explains why Pembrokeshire is one of the UK’s top surf destinations

IT’S STRANGE AND NOT ALTOGETHER UNWELCOME the way that some things seem to remain outside the mainstream. Body surfing, for instance, can never hope to enjoy the high profile that regular surfing has, and I have no doubt that the majority of its exponents are only too happy for things to remain that way.

It’s much the same with the surf scene here in Pembrokeshire – indeed, I expect there are readers who scanned that place name and were hit with the immediate response of “Where?”

This is a bucolic corner of the British Isles that has largely been bypassed by the media frenzy that now seems to surround surfing in this overpopulated archipelago. As I type this piece in late August I know for sure that at this very moment every single break in South West England, for example, will be populated by every form of surf craft ever invented, whether there are waves breaking upon the shore or not; meanwhile, I’m planning an afternoon of surfing in a small cove not more than two-miles from my home where it’s quite possible I’ll be the only person in the water.

It can indeed seem that you are in the world as it was when God was a lad as you sit on your board with a late summer swell rolling by, jade green water so clear you can see the sand several feet beneath your deck.

Quiet surf spots

Sure, there’s a bit of a compromise to be made in that the waves are rarely that good at ‘my’ break; on the other hand, the water will be warm enough for me to wear a shortie (a rare thing in this part of the world) and since I’ll probably be the only one out I’ll have my pick of the sets – and the occasional fast, walling little right or left is guaranteed at some point. For me that’s a compromise worth making – and, of course, there’s no way I’m gonna reveal the name of this little gem…

Even Pembrokeshire’s better known surf spots will be quieter than those of England’s southwest, even though they actuallly have a wave riding history that goes back fifty years or more. Despite this recent anthologies of British surfing and various surf guides rarely if ever make mention of the fact that people were riding waves at Freshwater West, Newgale and Whitesands only three or four years after the sport was ‘introduced’ to Cornwall and North Devon.

For instance, photos exist of members of Whitesands-based Porthmawr Surf Life Saving Club taken in the early sixties, when I seem to recall that the club was based in an old railway carriage – if there were dudes there to keep the surf safe, sure as eggs is eggs they were also riding it on old tankers.

The guy who showed me the pic is the venerable Dr. George Middleton of St. David’s, now in his eighties, still getting into the surf on an old belly board and responsible for two more generations of Middletons currently riding the now busy waves at Whitesands and elsewhere from California to the Maldives.

Freshwater West

Meanwhile, at the same time as the lifeguards of Porthmawr SLSC were dragging members of the public from the sea at Whitesands, Pembrokshire’s primo surf beach of Freshwater West was receiving regular visits from small groups of surfers based further east in Gower, Porthcawl and the Cardiff area. One of these was Paul McHugh, who was making rudimentary boards in the sixties before moving down to Pembrokeshire.

“I think I was one of the first down here,” he told photographer Adrian Lincoln, who’s work you see here. “The only two local surfers I remember are Bob Rodgers and Reg Goddard [Bob still surfs, as does Paul who also still shapes too].

“Then people started coming here from Cardiff. But there were no young people in Pembrokeshire – there was no work. There was a big shortage of people in their early twenties so I guess that’s why surfing never took off down here in the early days, and the holiday industry was unexploited too, unlike today. Fresh West seemed massive [surfing] on your own – you just wanted to surf with someone else! Then Pete Bounds [former British and Welsh champion] and Paul Ryder, who started in Porthcawl, moved down here and things slowly took off”.

Affable and laid back, Pete Bounds is still a mad keen surfer – I was chatting to him about his latest board at Whitesands just a few weeks ago, and he’s also taken the North Pembrokeshire grommets under his wing with his increasingly popular Surf Masterclass at Newgale; Paul Ryder, who was the county’s first board maker, unfortunately died some years ago.

Glory days

So those were in many ways the glory days that every other surf zone in the world has experienced at some point – just a handful of pioneers enjoying the waves on their own, discovering new breaks and riding the swells on rudimentary equipment – a situation most of us would swap for all our fancy modern boards and super stretchy wetsuits I reckon.

And yet this solitude is not entirely a thing of the past in Pembrokeshire…Adrian recalls how some of the shots featured here were only achieved after many miles of driving around the south of the county during a mid-week, mid-winter swell looking for a wave with a surfer on it to actually give the shot some context. Yet it’s not as if we have to endure Nova Scotia-like temperatures either in or out of the water.

It still is the case that this is a relatively thinly populated area, some distance from any major metropolis, where outside of peak season there are few enough surfers around that you can occasionally get a taste of those halcyon days of empty waves of the sixties and seventies.

Those visitors who pile down to Pembrokeshire in summer to jam up the readily accessible beaches with their body boards and pop-outs would be amazed to see how quiet it becomes once the sun (and many locals) have headed south for the winter. They’re here in their summer hordes partly because Pembrokeshire has in the last few years been showered with accolades from the likes of National Geographic Magazine, amongst which are ‘world’s second best coastline’ and ‘world’s third best long distance trail’, whilst various beaches have been rated amongst the world’s top ten.

Interestingly they fail to take into account an equally beautiful hinterland that consists of rolling green fields, quiet sunken lanes, deep green woodlands and high windswept hills from whence came the Bluestones of Stonehenge. And the fact is such ‘awards’ mean absolutely bugger all in reality (has anyone actually been to every coastline, trail or beach in the world in order to make a reasoned assessment?) but they do attract punters to what they think will be a pristine coastal environment and bring money into an economy that could never be said to have been particularly healthy.

It can indeed seem that you are in the world as it was when God was a lad as you sit on your board with a late summer swell rolling by, jade green water so clear you can see the sand several feet beneath your deck whilst grey seals pop up to watch the surf action from just a few yards away.

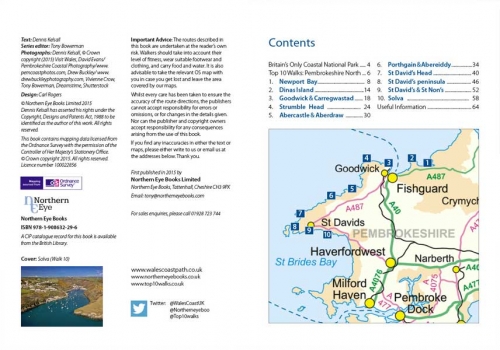

Gulfstream wildlife

We’re in Britain’s only coastal national park after all, a land blessed with internationally important seabird habitats on the various offshore islands; where dolphins, porpoise, whales and sunfish reside in the Gulf Stream warmed waters; and where even the peeling brown perfection you see in some of the pictures here is nothing more than the result of sand held in suspension following the storm that battered the waters to create the swell in the first place.

And yet…

National park this may be, but when our endless succession of venal and greed inspired governments first created the park and then set about administering it they ensured that in the legislation was a clause allowing any development deemed to be ‘in the national interest’ to go ahead, irrespective of its impact on this glorious coastline.

So we have a situation where you can be paddling into a clean four-foot swell at Freshwater West whilst an offshore breeze wafts the stench of chemicals from the nearby Texaco refinery across the beach; where a new gas plant in the same location will, on completion, give us a valuable new jobs – and CO2 concentrations to rival those of the infamous industrial coastlines around Port Talbot; and, of course, in 1996 we saw 73,000 tons of crude oil wash ashore at many of the best surf beaches after the captain of the Sea Empress oil tanker managed to collide with the local coastline.

It’s a story echoed around the world and one that will continue to echo as long as governments and economists labour under the ludicrous misapprehension that economies must continue to grow from now until the end of time.

The naivety of those who would hold forth on how to run our economy and our lives can easily be forgotten when you’re out in the surf, of course, because on the whole Pembrokeshire does a good job of hiding its less endearing nooks and crannies and instead presenting to the world the picture the tourist boards want us all to see of the languid surfer cruising along on an ‘Atlantic roller’, but it’s not quite as pristine as they’d like you to think.

‘Lowland Hundred’

In recent years the more discerning surfers of SW Wales have taken to heading north of Pembrokeshire to a land I shall describe only as Cantre’r Gwaelod, which translates as ‘The Lowland Hundred’.

This is a stretch of coastline that for many years was surfed by only a handful of local guys and an even smaller number of visitors such as ‘The Gill’ from Mumbles and his cohort ‘Guts’ Griffiths, former European longboard champ. ‘The Gill’ is one of those surfers who makes it his duty to research marine charts, weather charts, weather patterns, tidal flows and Ordnance Survey maps so that they know when and where to go on their surfaris, whether it be West Wales, the west of Ireland or south-west France.

In the case of ‘The Lowland Hundred’, ‘The Gill’ invariably succeeds in scoring some classic point breaks that for literally decades less knowledgeable surfers never really considered capable of picking up a decent swell.

The evocative name of the region comes from an ancient Welsh myth – there was apparently once a walled country offshore which was defended from the sea by a dyke; this flooded, the ‘Lowland Hundred’ was inundated and is no more, but the church bells of this mysterious land are still said to ring out in times of strife and in 1770 Welsh antiquarian scholar William Owen Pughe even reported seeing sunken human habitations about four miles offshore. Yeah, yeah…

But it’s a nice tale. And it’s a region that, although in places it can become overrun by surfers from far and wide on a good swell, can also still surprise those prepared to explore. It’s also an area compatible with another ancient Welsh phrase used to describe Pembrokeshire – ‘gwlad hud a lledrith’ (‘land of mystery and enchantment’) and it’s the one part of the region that you might still find something of the atmosphere and sensation experienced by the likes of Paul McHugh and Pete Bounds when they first ventured to Wales furthermost corner in search of surf.

This article first appeared in The Surfer’s Path magazine in October 2011, and is re-published here with the author’s permission. Copyright © Alf Alderson 2011. All rights reserved.

Alf Alderson is an award winning adventure travel journalist who shares his time between the Pembrokeshire coast and the French Alps. His work has appeared in a wide range of newspapers, magazines and websites including The Guardian, Daily Telegraph, The Times, South China Morning Post and Toronto Globe & Mail.

Alf is a member of the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild; and is available for commissions.