Steam engine on the narrow gauge Talyllyn Railway

Vivienne Crow explores the railways, castle, beaches and wildlife of the Snowdonia and Gwynedd coast

“GET YOUR HEAD IN! TUNNEL COMING!” Coal smoke wafted through the tiny carriage’s open windows, bringing with it a hint of times past, as the steam engine passed under a bridge on the Talyllyn Railway. The young boy with his head stuck excitedly out of the window pulled it back in hurriedly. It was half-term and the train was packed with animated families and ‘tracksiders’ glowing from a day of voluntary work along the line.

Railway fever

Adults seem as excited as the youngsters as the engine driver sounded the whistle on what proudly bills itself as the world’s first preserved railway. The seven-mile, narrow-gauge line was built in the mid-1860s to serve the Bryn Eglwys slate quarry on the edge of what is now the Snowdonia National Park. After the quarry’s closure in 1947, it seemed the line would be lost forever, but a group of enthusiasts stepped in, restored it and have kept it running ever since.

The ‘tracksiders’, proudly wearing their orange high-vis vests and sporting muddy knees and cheeks streaked with grime, are the next generation of volunteers. During half-term holidays, these family groups work on painting fences, clearing undergrowth, building footpaths in the woods beside the line…

On the second part of our two-centre trip to the Snowdonia Coast, as well as enjoying a ride on the Talyllyn Railway and paying visits to Tywyn and the lovely, laid-back town of Aberdovey, we spent some time exploring the beautiful Mawddach estuary.

“Leaves on the line”

“We’ve been clearing leaves from the paths,” a precocious 10-year-old explained to me. “It’s an endless job.” Meanwhile, as the train made its way down from Nant Gwernol, close to the foot of Cadair Idris, his father explained to another family in the carriage the intricacies of the guard’s coloured flag system. (Apparently, it’s not simply a case of ‘green for go’ or, in railway terminology, for the ‘right away’.)

The viaduct at Dolgoch was crossed as the train passed through the golden woods and then out along the base of slopes tinged with the bronze of dying bracken fronds. Surprisingly rapidly, we crossed the coastal plain and reached the railway’s terminus at Tywyn. Passengers disembarked, lingering on the platform to take pictures of the pristine engine, as red and shiny as if it had just come out of a Hornby box.

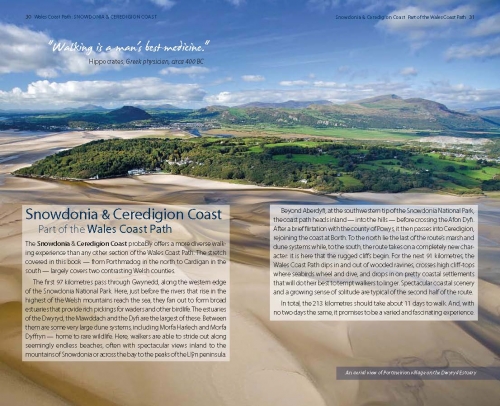

Railways, both historic and modern, seemed to dominate our trip to the Snowdonia coast. The National Park is generally associated with high, craggy peaks, but, all along its western edge, where the hills tumble dramatically into the Irish Sea, are some fantastic beaches, vast dune systems and beautiful, wooded estuaries sometimes cutting far into the heart of the mountains. And, wherever you go, it seems you’re never far from a working railway line.

Welsh narrow gauge railways

A few days before our trip on the Talyllyn Railway, we’d been walking in the densely wooded Vale of Ffestiniog. Every now and then, the haunting sound of the whistle of the Ffestiniog Railway echoed through the trees. In the darkest, loneliest parts of the forest, it sent a shiver down my spine, reminding me of barely remembered ghostly railway stories I’d heard as a child. But the occasional glimpses of puffs of smoke and the track-bed itself confirmed that, like the Talyllyn Railway, this historic line is alive and thriving.

Also like the Talyllyn, the Ffestiniog line was built to serve the slate quarries. The engineer was James Spooner, whose son, James Swinton Spooner, later went on to build the Talyllyn line. But that’s where the similarities end. While the Talyllyn chugs its way up a gentle incline with just one viaduct, the engines of the Ffestiniog Railway climb more than 700ft on their 13-mile journey from the former port town of Porthmadog to Blaenau Ffestiniog at the foot of the mountains. Right from the outset, where the railway passes over a mile-long stone causeway that has been holding back the sea since 1811, the engineering feats are apparent. They include impressive cuttings, embankments and a tunnel blasted through the mountains. I watched one of the engines labouring up into the hills, thinking about the ponies that, before steam came to the gravity-operated line, used to haul the empty wagons from the coast back up to the mountains’ mines and quarries.

Cambrian Coast railway line

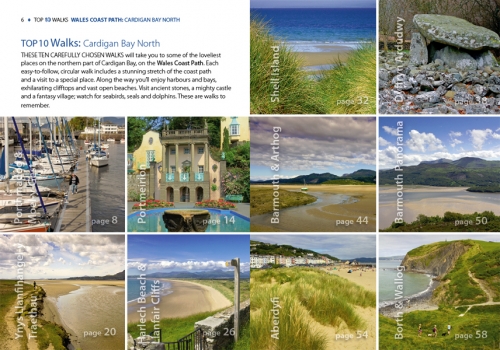

My partner Heleyne and I spent a few days based in Harlech and a few days in Barmouth as we explored this northern stretch of Cardigan Bay. Both towns are on the Cambrian Coast Line, which runs from Machynlleth in the south to Pwllheli on the Llyn Peninsula in the north. No steam trains here: this is a standard passenger railway, used by commuters and tourists alike. Deciding to leave the ’van hooked up for most of our trip, we got to know the line well as we set out each day to visit attractions and walk sections of the Wales Coast Path.

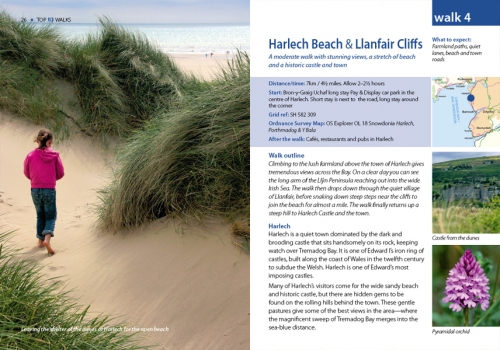

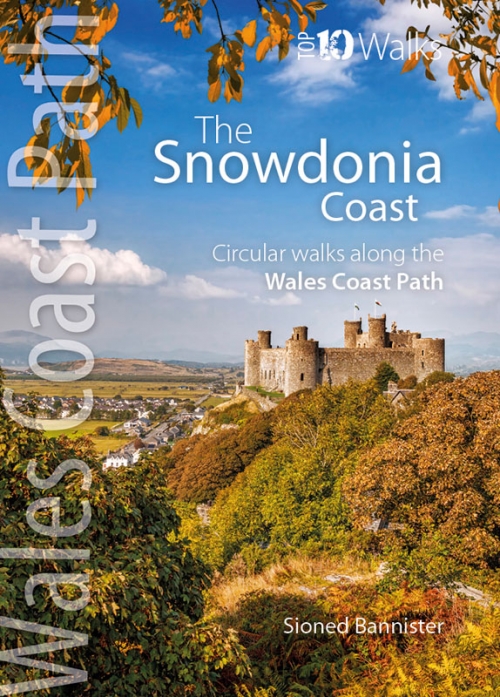

Harlech itself is dominated by the medieval castle that sits, impregnable, on top of an almost vertical cliff-face. It was built by Edward I in the late thirteenth century, a very visible reminder to the Welsh of England’s might. It was probably white-washed in Edward’s day, a formidable-looking apparition looming over the coast. Visitors can still explore its massive east gatehouse and become totally disorientated in the maze of dark stairways leading up to the battlements. I’d recommend taking a torch to light your way.

Our campsite was tucked in at the foot of the castle’s rocky vantage point. My pre-bedtime walks with our terrier Jess took on a surreal, dreamlike quality with the dark cliffs invisible and the floodlit walls and towers seeming to hover, suspended in the sky. Just imagine how bizarre it would look if it was still white-washed!

The campsite is in the lower part of the town, handy for the railway station. The main, higher part of the town is very much that – higher. The road leading up to the centre of town, known locally as the Llech, is said to be the steepest residential road in Britain. On our first ‘stroll’ up into the town, we paid a visit to the Tourist Information Centre where the assistant, Sian, was very keen to share her enthusiasm for this secret corner of Snowdonia. She pointed out various walks around the town and along the coast, and told us of some of the most spectacular viewpoints.

She wasn’t wrong about those views; they were often breathtaking – particularly from the long, dune-backed beaches that are spread all along this coast. On a walk from Harlech to Tal-y-bont, we quickly realised we’d chosen the wrong direction for this linear walk beside the sea. Heading south, we were constantly having to turn round to enjoy the scene to the north – the high mountains of Snowdonia on a clear day, including Snowdon itself, and the hills of the Llŷn Peninsula stretching far out into the Irish Sea.

Harlech dunes NNR

The dunes at Harlech are protected as a National Nature Reserve, and are home to a number of rare species, including the mining bee which burrows into the sand to build its nest. Sand lizards have also recently been reintroduced. We were visiting in the autumn, so we missed out on the impressive wildflower displays for which the reserve is also known.

On our walk south from Harlech, we also passed through another protected area: Morfa Dyffryn. Having negotiated the wetlands and dunes along the southern edge of Shell Island, known for their colourful orchids and population of great crested newts, we dropped on to a never-ending stretch of sandy beach. Not a soul in sight. The only movement, other than the rolling waves, were the large flocks of grey-and-white sanderling. Acting as a single unit, a flock would fly low over the beach, suddenly land at the water’s edge, rush around madly, plunging its many beaks into the sand in search of a tasty meal and then, just as abruptly, take to the air again to restart the process further down the strand. These curious birds kept us company as we continued south on our way to Tal-y-bont and the train back to Harlech.

Heading north on another day out from Harlech, we visited Portmeirion near Porthmadog. This whimsical Italianate retreat with its colourful buildings, fountains and rhododendron-filled gardens was built over a 50-year period, starting in 1925, by architect Clough Williams-Ellis. During the 1960s, it became the surreal setting for the cult TV series The Prisoner, starring Patrick McGoohan.

Ornate turrets, secret archways and brightly painted balconies all brought a touch of the Mediterranean to an otherwise dull day on the Welsh coast. With twilight closing in fast, we only had time to wander round the village itself and pay a quick visit to the gallery of one of my favourite landscape painters, Rob Piercy. On a previous visit though, I remember wandering through the pretty woodland of this rugged peninsula jutting out into the broad estuary. The views back towards the mountains of Snowdonia were magnificent. On that occasion, I’d also stumbled across the Dogs Cemetery, established by the eccentric Adelaide Haig, who lived on the peninsula from 1870 until 1917.

Mawddach Estuary

On the second part of our two-centre trip to the Snowdonia Coast, as well as enjoying a ride on the Talyllyn Railway and paying visits to Tywyn and the lovely, laid-back town of Aberdovey, we spent some time exploring the beautiful Mawddach estuary. On the grey afternoon we arrived in Barmouth, the seaside town looked tacky and uninviting while the estuary itself seemed a moody spot unlikely to appeal to anyone except birdwatchers, but when the next day dawned bright and crisp, it revealed a completely different side to the area. Having walked from the campsite on the edge of town and run the gauntlet of amusement arcades and the smell of doughnuts frying, we reached the harbour. While cafés and restaurants lined the waterside, the low cloud of the previous day had lifted to reveal the Cadair Idris range looming to the south-east. The golds, yellows and reds of the autumn trees, reduced to a uniform brown in yesterday’s gloom, seemed to shine in the sun.

But nature, however striking, takes a back-seat here, because the scene is dominated by the Barmouth Bridge. This grade II-listed structure is almost half-a-mile long. Built in 1867 for both rail and foot traffic, it consists of a largely wooden viaduct and a swing-bridge section that used to be opened to allow large ships to sail upstream. Pedestrians and cyclists used to have to pay a 90p toll to cross, but the couple who lived in the toll-house and were paid by the local council to collect the payments left in 2013 and are not likely to be replaced.

Barmouth Bridge

It should take about 10 minutes to cross the bridge, but I couldn’t help but dawdle, admiring the fabulous scene all around. Visible now for the first time were the hills that loom over Barmouth: the south-western reaches of the rugged Rhinogs. The gorse and bracken-covered hillside immediately above the town is Dinas Oleu. Acquired by the National Trust in 1895 and covering four aces, this was the conservation charity’s first parcel of land.

On the south side of the estuary, we took the Wales Coast Path west, beside the saltmarsh, to Fairbourne, home to yet another narrow-gauge railway. This one, however, was built not to service local industries, but to cater, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for the growing number of tourists visiting this part of Wales. We could’ve headed east from the end of Barmouth Bridge – along the 9.5-mile Mawddach Trail. Following the river upstream, this shared cycleway and walkers’ path skirts the edge of saltmarshes and mudflats rich in widlife, and passes through gorgeous woodland on its way to Dolgellau. Sadly, on this trip, we didn’t have time trip to walk this disused railway: we’d spent so long getting a taste for the working ones. Still, it looks to me like a good reason to return…

This article first appeared in MMM (The motorhomer’s magazine) in May 2015, and is re-published here with the author’s permission. © Vivienne Crow 2015. All rights reserved.

Vivienne Crow is an award-winning freelance writer and photographer specialising in travel and the outdoors. She has written almost 20 walking and travel guidebooks, contributes regular features to newspapers and magazines, and does copywriting for conservation and tourism bodies. Vivienne is a member of the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild, and is available for commissions.

Contact: viviennecrow@hotmail.com

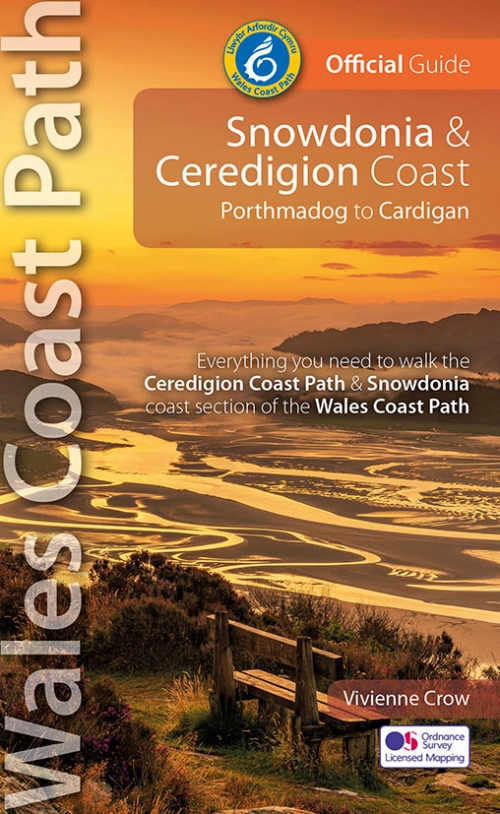

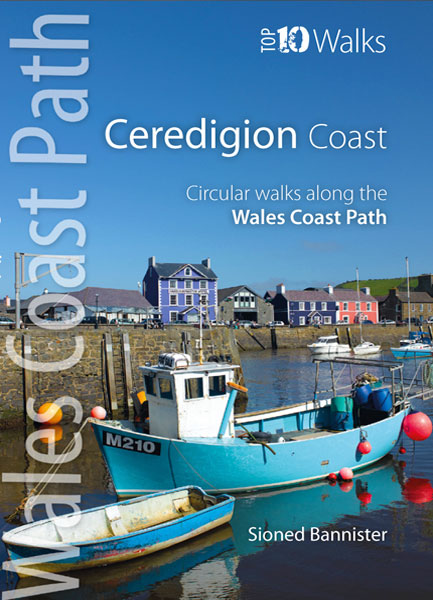

Books and maps for this part of the coast