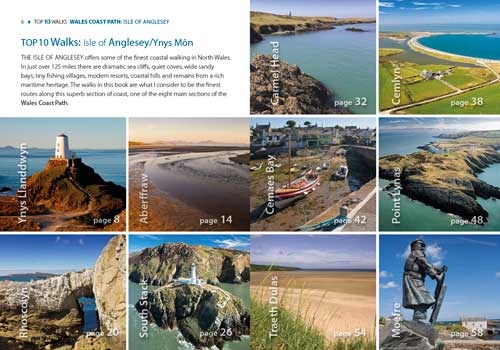

Moelfre is a tiny fishing village on the east coast of Anglesey

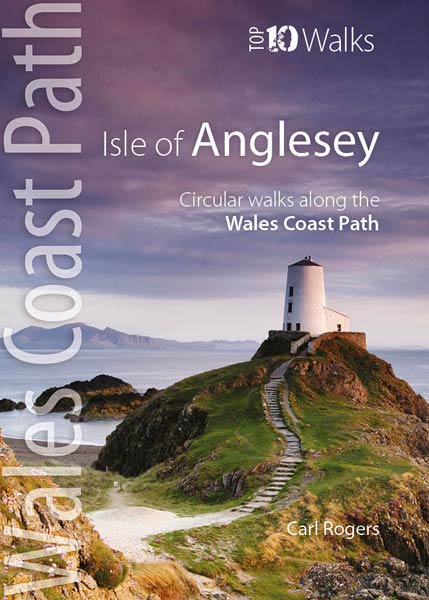

Discover shipwrecks and prehistoric monuments around Moelfre on Anglesey’s east-facing coast, says Carl Rogers

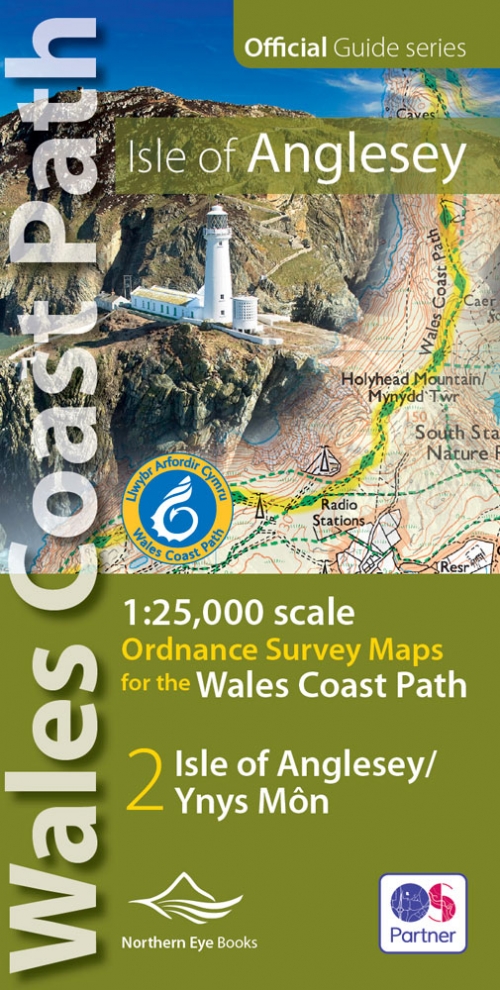

LOOKING AT A MAP OF WALES PINNED TO MY OFFICE WALL a few months ago, as I traced its coastline from the Dee estuary out along the North Wales coast to Anglesey and around the long arm of Llyn, then on down the graceful curve of Cardigan Bay, around the indented, craggy fist of Pembrokeshire, Gower, and finally the softer bulge of Cardiff Bay to the border at Chepstow, one thing struck me.

I suppose it’s an obvious thing in a way, but I hadn’t really considered it before: little, if any of this coast – almost 900 miles of it – is east-facing. The only exception is the Isle of Anglesey, where almost one third of the coastline faces east. This may seem a very mundane piece of information, but it explains why the east coast of Anglesey is so different to the rest of the island and indeed the rest of Wales. It was also a key element in one of the worst shipping disasters of the 19th century but more on that later.

Anglesey’s rare east-facing coast

The exposed nature of the Welsh coast defines both its character and its physical shape — its sea cliffs, its huge sandy beaches, its sand-dune systems, its stunted vegetation and its general lack of trees. These are all common features of coastal Britain as a whole — a rugged and beautiful landscape, one of the finest in Europe and the reason so many northern Europeans come to Britain to walk its coastal paths.

But back to Anglesey. You can divide the island’s coast into four distinct sections corresponding approximately to the points of the compass – north, south, east and west. Each is very different in character and the east coast is no exception. Turning its back on the prevailing westerly winds, it escapes the majority of the storms that sweep in across the Irish Sea. Instead of exposed, treeless headlands you have fields, hedges and woods – sometimes right down to the water’s edge. Different indeed.

Midway along the east coast is the village of Moelfre. It’s a small village, most of it built in the last 50 years or so. In its original form it would have been tiny — a handful of cottages arranged around a sheltered cove where a few fishing boats could be pulled up onto the shingle. In the holiday season it fills up quickly — a pub, a handful of tearooms, one or two gift shops and a tiny beach where you could just about swing a cat.

Moelfre

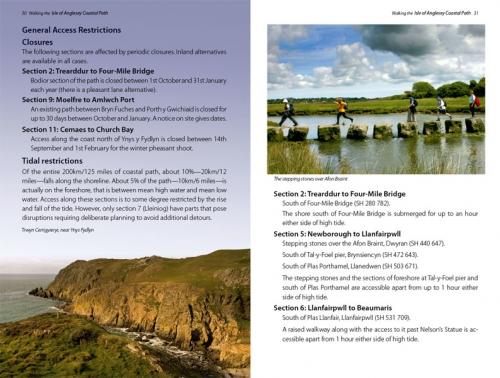

Unless you know Anglesey well, you are unlikely to have even heard of Moelfre, but in the mid-19th century it briefly became a household name for all the wrong reasons. In 1859 one of the worst shipping disasters of the century occurred here when the ‘Royal Charter’ was driven ashore by a freak, once-in-a-lifetime storm and the area became the focus of the national press. You can visit the site of the shipwreck along with an inland loop walk that also takes you to some of the finest prehistoric remains in Wales in an easy 4.5 mile walk starting at Traeth Lligwy, a superb beach, a mile or two north of Moelfre.

The large beach car park is busy in the holiday season, but there will probably be room on all but the busiest of days.

“A storm was gathering, an unusually fierce storm and it was approaching not from the west as normal, but from the east.”

The Walk

From the car park, head right along the coastal path which is well-defined and gives a fine view of the wide sweep of Traeth Lligwy with Ynys Dulas beyond. The first cove – Porth Forllwyd – is private and the path takes you beside a wall around the bay, before the path rejoins the coast to run along a series of low limestone cliffs. On the approach to the small shingle inlet of Porth Helaeth, look to your right where a small stone memorial commemorates the wreck in 1859 of the ‘Royal Charter’: ‘This stone commemorates the loss of the steam clipper ‘Royal Charter’ which was wrecked on the rocks nearby during the hurricane of 26th October 1859 when over 400 persons perished. Erected by public subscription in 1935.’

The memorial overlooks the rocks where the ship was pounded to pieces and can be approached by a short field path on the right, just before the beach. Looking around it’s hard to see why the event was such a disaster. There are no towering sea cliffs or off-shore reefs to tear a ship apart, just a rather mundane shingle cove where the water is quite shallow. It seems the ship was incredibly unlucky. In its day, the ‘Royal Charter’ was one of the fastest clippers on the run between Liverpool and Australia. In late August 1859 it was on the return voyage and had sailed halfway around the globe, almost 16,000 miles. It had safely navigated the Cape and dealt with the stormy seas of the South Atlantic. It had passed the Cornish coast, the hazards of Pembrokeshire and Lleyn, and the dangerous north coast of Anglesey was now behind it. There was just 50 miles to its home port of Liverpool – plane sailing.

Freak Storm

It was the middle of the night and they would be in port by be morning. Then came the first piece of bad luck. A storm was gathering, an unusually fierce storm and it was approaching not from the west as normal, but from the east. This was, and still is, extremely rare. Sailing ships can’t sail directly into the wind so the ‘Royal Charter’ had an auxiliary engine to assist its sailing rig. With the sails down this would normally have carried it into port, albeit a little slower against the wind. But this was no ordinary storm and as it gathered strength it became clear that the engine was not powerful enough and eventually failed altogether.

Out in the ocean a ship of this size would probably have coped even with these freak conditions and if it could have turned tail and headed out to sea it would have done. The only option was drop anchor and try and ride out the storm. This was done, but the anchor chains broke and the ship was then helpless. Driven southwest it was heading directly for the next piece of bad luck — the only sizeable section of coast in Wales that faces east! In the dark those on board could only guess what lay ahead. The crew no doubt hoped beyond hope that they would be blown out into the Irish Sea. As it turned out the ship came ashore here at Porth Helaeth. There must have been a sense of relief at first, but more bad luck was on the way.

The tide was low but rising and initially the ship ran aground on the sandy floor of the bay a few hundred yards out. Had the tide been falling she would have ridden out the storm, battered and bruised, but probably in one piece. As (bad) luck would have it the tide was rising and gradually the ship was lifted off the sandy floor and carried onto the flat, gently sloping rocks on the far side of the cove.

Wreck of the ‘Royal Charter’

When the ship broke those on board were thrown into the water where most were battered to death on the rocks just a few feet from safety. In total 465 lives were lost and there were no women or children amongst the handful of survivors. Grim indeed and what incredible bad luck! It was the worst storm of the century blowing in from the east, towards the only sizeable section of eastfacing coast in this part of Britain, along with the worst possible tidal conditions.

The nation was shocked. Charles Dickens came here to report the events and tales of villagers plundering the bodies washed ashore ran riot. A local country vicar — Rev Stephen Hughes — spent weeks trying to identify the broken bodies for grief-stricken families and his little church became a temporary mortuary packed with the dead. The events, it seems, led to an early grave for him. He died shortly after at the age of 47 and is buried along with many of the victims in the cemetery at Llanallgo a mile or two inland from Moelfre.

Beyond the cove, the footpath rises to a caravan site then bears left to continue along the coast to open land on a small headland with Ynys Moelfre ahead across the narrow channel of Y Swnt. Further along, a signpost directs you onto a small shingle beach by cottages and at the far end you are directed right immediately before a cottage. Follow the path past the lifeboat station and Seawatch Centre, which houses an exhibition of sea rescue, along with the RNLI lifeboat ‘Bird’s Eye’. This craft was presented to the RNLI by Birds Eye Foods Ltd and was used for over 20 years between 1970 and 1990 in New Quay. It was launched 89 times and saved 42 lives. Beyond the Seawatch Centre, the path bears right to Moelfre harbour. Join the road here and turn left along the front, then up the hill passing the ‘Kinmel Arms’ on the right and the anchor taken from the wreck of the ‘Hindlea’, lost on October 1959 almost 100 years to the day after the loss of the ‘Royal Charter’ and in almost the same location.

Take the first road on the right and continue for approximately . mile. Immediately after the entrance to quarry workings on the left, turn left through a kissing gate onto a signed path. Rise to a second kissing gate and follow the right of way ahead along field edges. In the far corner of the second field, turn right along the field edge to a quiet lane.

Prehistoric sites

There are three remarkable historic sites nearby which are well worth visiting. The first is the Lligwy Chamber thought to date from the late Neolithic period. To visit the chamber turn left here and follow the lane for about 300 yards. The chamber lies in fields to the right. The most obvious feature of this burial chamber is the massive capstone: over 18 feet long and nearly 16 feet wide. It is estimated to weigh around 25 tons and was probably lifted into place with the aid of timber scaffolding. Two thirds of the chamber lie below ground level and make use of a natural fissure in the rock giving the chamber a very squat appearance. The entrance faces east towards the lane and originally the whole structure would have been covered by a mound of earth and stones that has been eroded away over the centuries.

Excavations in 1909 revealed the unburned remains of up to 30 individuals as well as animal bones and pottery. The form and decoration of the pottery suggests that the chamber was in use during the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age periods.

Retrace your steps along the road passing the spot where you entered the lane. Beyond this, look for the signed footpath to ‘Din Lligwy’ and ‘Hen Capel’ on the left. The path keeps beside the fence on your left with the ruins of Hen Capel to your right. A metal kissing gate takes you into a small wood where a short rise leads to Din Lligwy.

Din Lligwy is a remarkable place. It is one of best-preserved British settlements in the country and is thought to date from a period when the Romans were withdrawing from North Wales — around the middle of the 4th century. It is most likely to have been the dwelling of a local chieftain or ruler and consists of a total of nine buildings; seven rectangular and two circular, which would originally have been thatched. The entrance is at the eastern end and a defensive wall some five feet thick surrounds the site (which covers about half an acre. The two circular buildings are thought to have been dwellings, the rectangular huts were most likely barns or workshops.

Retrace your steps to the lane passing Hen Capel, standing alone and isolated in the fields overlooking the bay. Hen Capel or ‘Old Chapel’ dates from the twelfth century when most early Celtic churches were built in stone for the first time, replacing earlier wooden structures. By this period Anglesey was finally free from the fear of Viking raids and the lower parts of the walls survive from this time. The upper half of the walls were built 200 years later and additions were also made in the 16th century. Inside, the walls were originally rendered although little remains today.

To complete the walk return to the lane, turn left and at the crossroads go straight ahead returning to the beach car park.