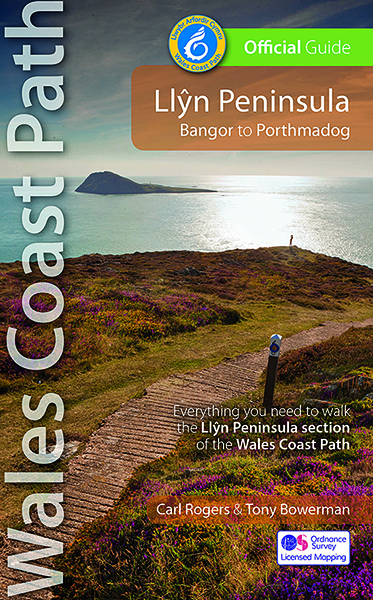

The view towards Bardsey Island, or Ynys Enlli, on the Llyn Peninsula

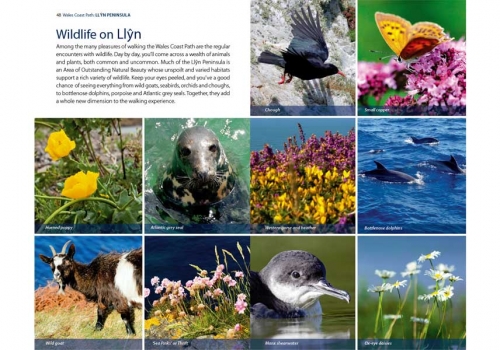

The Llyn Peninsula section of the Wales Coast Path is a quiet place rich in prehistoric sites, wildlife and silences. Vivienne Crow enjoys a few days’ peace.

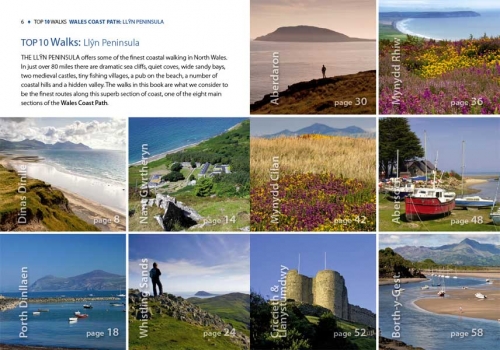

A SENSE OF BEING ISOLATED FROM THE OUTSIDE WORLD is, for me at least, one of the key attractions of the Llŷn Peninsula. It’s not an easy place to get to. Once you’ve come off the North Wales Expressway, there’s just one last stretch of decent A-road before you find yourself on increasingly narrow lanes that lead slowly – ever so slowly – into a pastoral landscape where time seems to be standing still. The hills, cliffs and heathland, so often shrouded in wraiths of mist, are covered with historic remains, including dozens of enigmatic prehistoric sites; and the tiny fields are divided by traditional, stone-faced earth banks known as cloddiau. It doesn’t look like the twenty-first century and it doesn’t feel like it either.

This slender finger of land reaching out towards Ireland at the north-western tip of Wales is watched over by two castles guarding either side of the neck of the peninsula – Caernarfon and Criccieth. Most motorhomers will pass one of them as they head out on to Llŷn. As we approached from the north, it was Caernarfon Castle that accosted my partner Heleyne and me soon after we left the A55. Despite the rain, we felt obliged to pay our respects to this massive, well-preserved fortress.

As we headed south-west, it was like travelling further and further back in time.

Caernarfon Castle

Built in the late thirteenth century, it was part of Edward I’s ‘iron ring’ of castles in Wales, using a formidable combination of concentric defences, barbicans and large gatehouses. A highly visible reminder to the unruly Welsh of England’s might, each castle was planned with its own walled bastide town populated solely by English settlers – local people were allowed to enter, but only during daylight hours and they had to be unarmed. The town battlements at Caernarfon survive intact today, including towers and impressive gateways. Although visitors can’t actually walk onthe medieval walls, you can follow them on a circuit of the old town. We considered it but, with the rain intensifying and the rest of Llŷn calling, we pushed on…

As we headed south-west, it was like travelling further and further back in time. As well as the ancient remains littering the landscape, mobile phone signal became increasingly patchy and the roads quieter and slower. I was forced, literally and metaphorically, to move down a gear. No bad thing. It felt like I’d gone back to another, less frantic era. Time to explore at an unhurried pace, time to stop and watch the wildlife, time to relax…

A few miles beyond Caernarfon, as the rain started clearing, we stumbled across the first of many hidden gems. St Baglan’s, near Llanfaglan, is a redundant church looked after by the playfully named Friends of Friendless Churches. It’s just a short walk from the road, and yet it has a sense of timeless seclusion. Inside are some gorgeous wooden box pews and benches dating from the middle of the eighteenth century. As I snapped a few photos, I half expected families, all done up in their Sunday Georgian finest, to take their usual seats. At one time, apparently, there was a healing well in a nearby field, particularly good for getting rid of warts. Sufferers were encouraged to bathe the affected area, prick it and then drop the pin into the well. Hundreds of pins were discovered when the well was dredged in the nineteenth century.

‘Town of giants’

Further down the peninsula’s north coast, we leapt back in time again when we visited one of the best preserved hill forts in Britain. Tre’r Ceiri is located on one Yr Eifl, or The Rivals, a rocky, volcanic dome that’s often mistaken for the higher mountains of Snowdonia when seen from a distance. I first visited the fort several years ago, on a misty day, and my hazy memory was of tremendous walls, both thick and high, encircling a huge settlement of clearly discernible houses. I had assumed my memory was blurred by a combination of the disorientating physical mist and the more whimsical mists of time. But no… On my second visit, having climbed up to the enclosure via a narrow, rock-walled corridor, I passed through the inner wall and could see it was just as sturdy as I remembered – almost 12ft high in places – and the remains of the buildings were more substantial than anything I’d seen on mainland Britain. Archaeologists tell us the oldest settlement dates from the Iron Age, although it was built around an even earlier Bronze Age cairn. It then grew during the Romano-British period. In the silent solitude, it’s hard to believe as many as 400 people lived in the 150 houses unearthed here.

Also on the north coast, Porth Dinllaen is well worth a visit. A track leads from the National Trust car park at Morfa Nefyn along a narrow, grass-topped promontory that, like so many Llŷn hills and headlands, is crowned by the remains of an Iron Age settlement. From the rocks at the tip of this cape, we watched grey seals immediately below us. The sea was so clear we could easily make out the creatures’ long, blubbery bodies as they floated near the water’s surface.

A rocky trail led us along the base of the cliffs on the headland’s eastern side to a tiny fishing village. Despite having no vehicular access, it was a busy spot on this hot summer’s day, its sheltered waters filled with swimmers, kayakers, paddle-boarders and sailors. We had to pick our way through the blubbery bodies (human this time, not phocine) spread out in front of the Ty Coch Inn, which sits just a pebble’s throw from the sandy beach.

Our base for exploring Llŷn was Ty-Newydd Farm, home to one of the many campsites at the far end of the peninsula, a Welsh-language stronghold known as Uwchmynydd. It takes a while to get anywhere from here – this is about as far along the peninsula as you can get – but the friendly site and its surroundings made it well worth the effort.

Overlooking Bardsey – ‘island of 20,000 saints’

On one of the highlights of the trip, we walked from the campsite on a 10-mile circuit of the rugged cliffs of Uwchmynydd – along the north coast, across the neck of the headland to Aberdaron, where the poet R S Thomas used to preach, and then back along the south coast. It was a walk of open heathland, secretive coves, fort-topped headlands and wave-sculpted cliffs, following the reassuringly well-signposted Wales Coast Path for most of the journey. The high point, in more ways than one, was Mynydd Mawr (Welsh for ‘great mountain’) where heathers and western gorse creep along the ground, prevented from growing to any significant height by the salt-laden winds that almost constantly batter this exposed hill. From here, we were able to look back up the peninsula to Yr Eifl and out to sea to Ireland’s Wicklow Mountains on the hazy horizon. Closer in, just a couple of miles offshore but still a choppy boat trip away, was Bardsey Island, or Ynys Enlli.

Resembling a child’s drawing of a humpback whale, this is a special site in the religious history of Wales. A place where legend and history collide, Bardsey is thought to be the site of a Celtic monastery – one of the earliest in Wales – although the remains of the Augustinian abbey that survive on the island today date from the thirteenth century. It’s also said to be the burial place for 20,000 Welsh saints. In medieval times, three pilgrimages to Bardsey were the equivalent of one to Rome, and pilgrims flocked to the island from all over Britain, secure in the belief that, if they died there, they’d be guaranteed a place in heaven. Hospices caring for the sick and dying sprang up next to churches along the pilgrims’ routes – not as altruistic as it sounds; the ‘carers’ would’ve charged a fee.

We visited one of these churches on another walk that also took in part of the Wales Coast Path. Setting off from the car park at Porth Neigwl, or Hell’s Mouth, we passed through Llanengan, home to the delightful St Engan’s. As well as having a beautiful, carved rood screen and loft, the church contains a wooden money chest that was brought from the abbey on Bardsey following Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries.

From Llanengan, our route took us into the popular resort of Abersoch, sometimes sniggeringly referred to as Cheshire-on-Sea. While families played in the sand, on the waters of Cardigan Bay, adrenaline junkies on jet skis and power boats left in their wake those in yachts and on paddle boards seeking a more sedate ocean experience. It was quite a contrast to our previous walk but slowly, as we made our way up on to the cliffs, the noise, the speed, the bustle, all started to seem like a distant memory.

Choughs- ‘red-legged crows’

We watched as two adult choughs used their curved red bills to prise insects from the ground to fill the constantly squawking mouths of their two demanding youngsters. Further round the same headland – Mynydd Cilan, the southernmost on Llŷn – we saw another chough trying to intimidate two juvenile kestrels sitting on adjoining fence posts. They were indifferent to its warning swoops and dives, and the crow gave up when a parent kestrel flew in and sat on the rocks nearby, keeping a watchful eye on its offspring. Even though they’re rare in much of the rest of the UK, we saw several choughs on our trip; it’s not surprising the bird (known in Welsh as brân goesgoch, literally red-legged crow)is the symbol of the Llŷn Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Abersoch isn’t the only resort on Llŷn’s south coast. Nearby is Llanbedrog, known for its long line of colourful beach huts. Sadly, the traditional huts were all sitting in the car park when we arrived, having been rescued from the beach after the Beast from the East wreaked havoc there. The storm swept away tonnes of sand, lowering the level of the beach by about 60cm and leaving the huts vulnerable to flooding.

Further up the coast, Pwllheli was a useful pit-stop for stocking up on groceries, but we didn’t linger for long. Criccieth, on the other hand, turned out to be a charming place to spend a few hours. En route, we made a short detour to Penarth Fawr, where a tiny medieval house, now used for weddings, stands in a tranquil spot surrounded by trees. Nearby, the village of Llanystumdwy, the childhood home of David Lloyd George, plays host to a museum dedicated to the only British Prime Minister to have spoken English as a second language. The museum includes Highgate cottage, which has been furnished to look like it would’ve during the 1860s and ’70s when Lloyd George was growing up here.

Llanystumdwy is less than a five-minute drive from Criccieth, a seaside town with a magnificent mountain backdrop. It felt like a friendly, laid-back place as we wandered around and had a leisurely lunch in a little café near the railway station. This is a place of boutique shops, traditional tearooms, galleries and stylish but relaxed restaurants. But our main reason for visiting Criccieth was to see the castle. It’s nowhere near as substantial as Caernarfon. There’s no chance here of strolling along the castle walls or climbing one tower after another – this really is just a ruin – but it occupies a spectacular location. Built in the first half of the thirteenth century by Llywelyn the Great, it stands atop a steep-sided headland with amazing views in all directions. One minute I was staring out across the waters of Cardigan Bay, next it was the rocky summits of Snowdonia that drew my gaze, but it was the outlook to the west that really commanded my attention – beyond the town’s elegant beachside terrace of four-storey Victorian houses, Llŷn stretched away into the distance.

This was a place that’d kept us captivated for nearly a week and now, looking back along the peninsula, I felt we’d only scratched the surface.