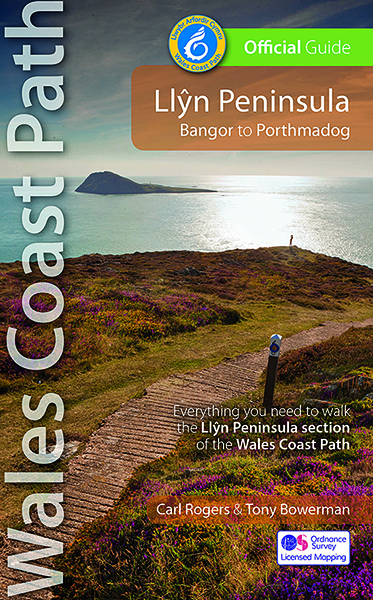

Nant Gwrtheyrn’s old quarrying houses, now a busy Welsh-language Centre on the Llyn Peninsula

On the Llyn Peninsula, beside the Wales Coast Path, lies a hidden valley. Here, during the Dark Ages 1,500 years ago, came Vortigern, the disgraced leader of the Romano-British, to hide from his enemies. Tony Bowerman came along later.

AS WE LEAVE THE TINY POST OFFICE in Llithfaen they lock the door behind us. It is two minutes past midday, yet the light is an ethereal, luminous grey. “Good afternoon”, calls a lilting voice through the door glass. The ‘Closed’ sign swings to a slow halt.

An old man, well-wrapped against the damp, leaves just before us. He carries a single bottle of milk and shuffles across the fog-dewed road. ‘Cold day’, he observes cheerfully as we pass.

He’s right. The cloud is down upon the mountain today, and the whole village is shrouded in muffled grey. At 900 feet above sea-level, and backed by the distinctive triple peaks of Yr Eifl, Llithfaen on the Llyn Peninsula, in Gwynedd, seems a curious place to choose to live.

You wouldn’t believe it’s the middle of July.

Vortigern, despised and neglected on all hands, retired to his own town in Radnorshire, which being burnt by his enemies in the hope that he would perish in the flames, he fled for refuge to the almost inaccessible retreat, at the foot of the mountain Rivel.

Celtic outland

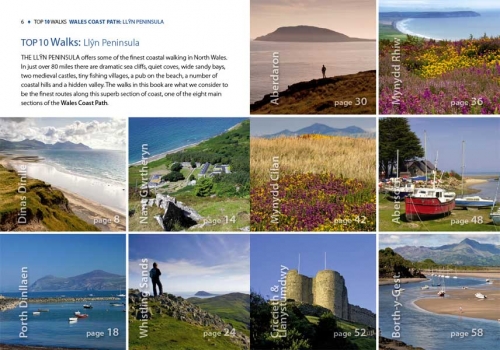

Yr Eifl, ‘The Forks’, known to the English as ‘The Rivals’, rise to 1,850 feet, and dominate the dragon-backed silhouette of this Celtic outland. The Llyn is a lucky cul-de-sac: the roads lead only to Bardsey Island, or Ynys Enlli — the ‘island of 20,000 saints’ and once a centre of pilgrimage — and so it is left alone. In its solitude, the peninsula boasts perhaps the greatest concentration of prehistoric sites and stone monuments anywhere in Britain. It is a place imbued with a sense of time: half-close your eyes and you might be back 3,000 years, lost in the middle of the Bronze Age.

From Llithfaen, a tiny unclassified road crawls up through a last straggle of houses and then winds across open heather moor. Sharp spikes of sedge loom in the mist, counterpointed by the dull hummocks of rock that rise from the wiry grass like lichened sheep. The cloud has a clammy grip on the earth, and ancient drystone walling snakes away into stillness.

As we walk, we ruminate over how many man-hours these walls represent; we conclude also that they endure for generations. Such walls, labouring over impossible ground were a long-term investment, a statement of future certainties.

Impressive hill fort

Away to our right runs a boggy path curving up to Tre’r Ceiri, the ‘Town of the Giants’. It’s a steep ascent — we climbed it yesterday. Here, across the summit of the most easterly of ‘The Rivals’, lies one of the most dramatic and impressive of the British hillforts. A vast oval wall, in places still 15 feet high and 16 feet broad, encloses a huddle of sturdily built stone huts. Perhaps 600 people lived here during the Roman period and on into the Dark Ages, safe from the ravages of Irish raiders. In summer the views are spellbinding. On a clear day you can see the Great Orme to the north; Dyfed away to the south; Snowdon, Cader Idris and Plymlimon; and out across the sea, the Wicklow mountains of Ireland. Yet in winter it must have been bleak beyond belief.

For us, the path runs north, down to the sea. There is almost total silence now among the rolling wraiths of mist. We stop and listen: invisible sheep, gulls mewling above the deep, the sound of our own ears.

Beyond lies Graig Ddu, the black rocks, falling in plunging wetness to the valley floor. The cliff is enwrapped to the rim in close-ranked conifers. Among the dark pines the faintly resinous air is still yet grainy: it is as if we are peering into a photographic enlargement taken on fast film. The air is full of jostling vapour. And the silence, as we tread on a carpet of pine needles, is almost tangible.

Porth y Nant

This is the edge. Below lies a secret valley, almost inaccessible except from the sea. It is called Porth y Nant. Once there was only one way down, by Bwlch Gwrtheyrn — Vortigern’s Pass. For it was to this remote fastness that Vortigern, Gildas’ ‘Proud Tyrant’, over-king of the Romano-British, it is said, came to die.

When Rome, with Alaric the Visigoth at her gates, at last in AD410 pulled back its troops and told the British they must fend for themselves, the Dark Ages had begun. Hard pressed by Pictish and Irish raiders, the Britons chose Vortigern as their leader. Mistakenly, he hired Saxon and Jutish mercenaries to pushback these northern tribes, but the two Saxon leaders, the notorious Hengist and Horsa, once here, decided to stay. The trickle grew to a flood: boatloads of Anglo-Saxons began to arrive, brining their wives and families to settle. Soon much of the south-east of England was under Germanic control, and Vortigern rapidly fell from favour.

Smollet, writing his Complete History of England in 1758 continues the traditional story:

“Vortigern, despised and neglected on all hands, retired to his own town in Radnorshire, which being burnt by his enemies in the hope that he would perish in the flames, he fled for refuge to the almost inaccessible retreat, at the foot of the mountain Rivel, where he spent the remainder of his life in continual terror and anxiety…. There was but one retreat over the mountain, so narrow as to admit only three persons to walk abreast with the utmost difficulty.”

Nant Gwrtheyrn

A chattering stream, Nant Gwrtheyrn, tumbles into the valley; in later days a tortuous and treacherous ‘Screw Hill’ or track followed the same route down. Now a still steep, but soulless road has been blasted out of the rock: it traverses the pine-clad crag with small regard for spirit of place.

Away from the world, it seems hard to believe that here, beneath Yr Eifl, was the epicentre of the earthquake that shook northwest Britain early in the morning of 19th July 1984. It was the strongest tremor in this country for over 100 years: 5.4 on the local-magnitude scale. The Llyn Peninsula suffered hunderds of aftershocks; yet today the rock screes that line the sides of the valley seem stable enough.

For many years Porth y Nant was an important quarrying centre. Most of the workers tramped daily over the mountain from Trefor: a miners’ village austere in appearance to outsiders, yet friendly to its inhabitants. In the valley gaunt reminders of the quarrying remain: a sea-decayed loading pier, a derelict crushing plant, and a rust-red truck incline.

Welsh-language Centre

The old quarry-owner’s house, staring eyeless out to sea, and the stone-workers terraces are now being converted for use as a Welsh-language centre. Yet, for now, the valley remains silent, mute in any language.

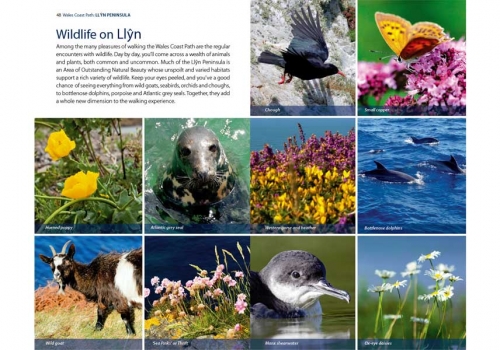

At the far north-east end of the shingle beach, grey seals bask on the half-submerged rocks as the tide turns, and gaze inquisitively at us. High above are the remains of a stone fort built looking out to sea. Now it looks down only over Bird Rocks, the nesting site for thousands of seabirds, whose harsh cries echo from the cliffs. Perhaps Vortigern stood here gazing out over the sea from his valley of exile.

For, as Smollet says:

“There is a hillock covered with a heap of stones, known by the name ‘Bedn-Guortigern’, the grave of Vortigern; which t eh inhabitants of Llanhaynon, digging up a few years ago [ie: in the 1740s], found a stone coffin, containing the skeleton of a very tall man.”